© 2024 Think Social Publishing, Inc.

Motivation is fundamental to our lives, and yet we often take it for granted. We depend on it for ourselves and for others at home, at school, at work, and in our communities. Motivation must be present for things to get done—mundane or spectacular—and to achieve goals of all shapes and sizes. Yet, as vital as motivation is to our all our efforts, finding motivation to undertake boring, mundane, difficult, time-consuming, or confusing tasks is rarely, if ever, taught explicitly. So, how do we help and support our students, clients, family members—or ourselves—who struggle to rally the motivation to get things done? What stands in the way of an individual’s motivational drive, and how can it be overcome?

Most of us are intuitively motivated to do things we prefer and enjoy; this type of motivation is called “intrinsic” since our motivation comes from within. On the flip side, it’s common to struggle to rally our motivation for things that are difficult, multi-stepped, require a lot of thought or time, or when we’re feeling down. We also tend to lack motivation for things we find boring, mundane, or tiresome; or things we don’t value, such as homework or a specific work project; or things we wish we didn’t have to do such as cooking dinner every night or cleaning up. At times like these, we require extrinsic motivation, which, at its most basic, involves rewarding ourselves. Often, it seems when it comes to rallying our motivation, the rewards can take many forms. I recently polled my friends and colleagues to find out what ways they reward themselves. Many found that they use metacognitively based strategies that have the “reward” built in. Here are some of the many ideas I gathered:

- Imagine feeling better once you get done with what you don’t want to do.

- Get organized to approach tasks as efficiently as possible!

- Break things down into smaller segments, create a checklist, and then mark off each step of the way once completed.

- Have good time management. Plan to accomplish things during a certain time of the day or date on a calendar. Predict how long things may take to accomplish to help you understand how much time you need to devote to a task to avoid feeling overwhelmed by it.

- Recognize that once you get in motion, it’s easier to stay in motion, meaning it will feel better to you once you start doing it.

- Begin by doing simpler things to warm yourself up to the bigger projects you need to tackle.

- If you’re a procrastinator, start by tackling the “low-hanging fruit” to feel good about getting something done.

- When doing chores at home, play a game in your mind. Imagine you’re getting paid for doing these to help you avoid getting distracted by so many enjoyable alternatives.

- And, of course, establish external reward systems to treat yourself when you’ve met a certain goal-based milestone.

In her article, How Motivation Works in the Brain: Exploring the Science, Elizabeth Perry defines motivation as “the force that causes us to act on our desires or fears. It’s what inspires and energizes our behavior to advance toward our goals, even when internal or external influences get in the way.” The reality is that many of my clients have lagging motivation to address challenges they feel they have in developing and maintaining relationships, and/or developing and maintaining organizational and time management skills that help them to be productive and satisfied with their accomplishments. As my clients become increasingly aware that they are not “keeping up” when they compare themselves to others, they may get sad, depressed, or anxious and become increasingly discouraged. As we unpack what they feel their problems are and goals they’d like to achieve, it’s not uncommon for them to say, “I tried some things to help me with this when I was younger, and they didn’t work for me.”

Here’s an example. I was working with a 28-year-old client recently who wanted to relate to more people because he currently has almost no friends outside of his family. To that end, I encouraged him to greet people in his community, such as the cashier at the grocery store, as a way of showing others he’s part of the community and that he includes others in his community. His first reaction was to say, “I used to be friendly to other kids at school, but they were never nice to me.” So, I asked him, “What have you learned at 28 years old that your 16-year-old self didn’t know or understand about relating to others?” He replied that he hadn’t thought about it that way and was willing to give it a try. In short, a good way to support someone’s motivation is to help them know that their learning never stops, that, in fact, their competencies improve across their lifetime. Many of my clients think that they don’t learn to help themselves past the years of their formal education. We discuss how social emotional learning spans a lifetime because it’s developmentally based. When older people are described as “wise,” it’s not because they are better at math or writing. Instead, it refers to how people are more aware of the nuanced social emotional skills that help them and others to be satisfied, if not happier, in their lives.

For those who struggle to rally their motivation because they are dealing with compelling sadness and depression, a medically reviewed article on Healthline.com offers some practical, doable tips:

- Get out of bed and out of your pajamas.

- Go for a walk to help release endorphins.

- Eat fermented foods, bacteria found in food such as yogurt, to helps to enhance moods by reducing anxiety and potentially improving symptoms of depression.

- Don’t overschedule and congratulate yourself for every task or goal you complete, no matter how small.

- Avoid negativity: your brain digests whatever thoughts you create, so feed it positive ones.

- Stick to routines.

- Socialize.

- Create a support network or become part of an existing one. There are many different online support groups that help us to feel that we are part of a community.

- Get enough sleep.

The article also recommends that you develop a mindset of persistence. This will be the hardest to do as you establish this routine, but over time, it becomes easier to rally your motivation to get things done.

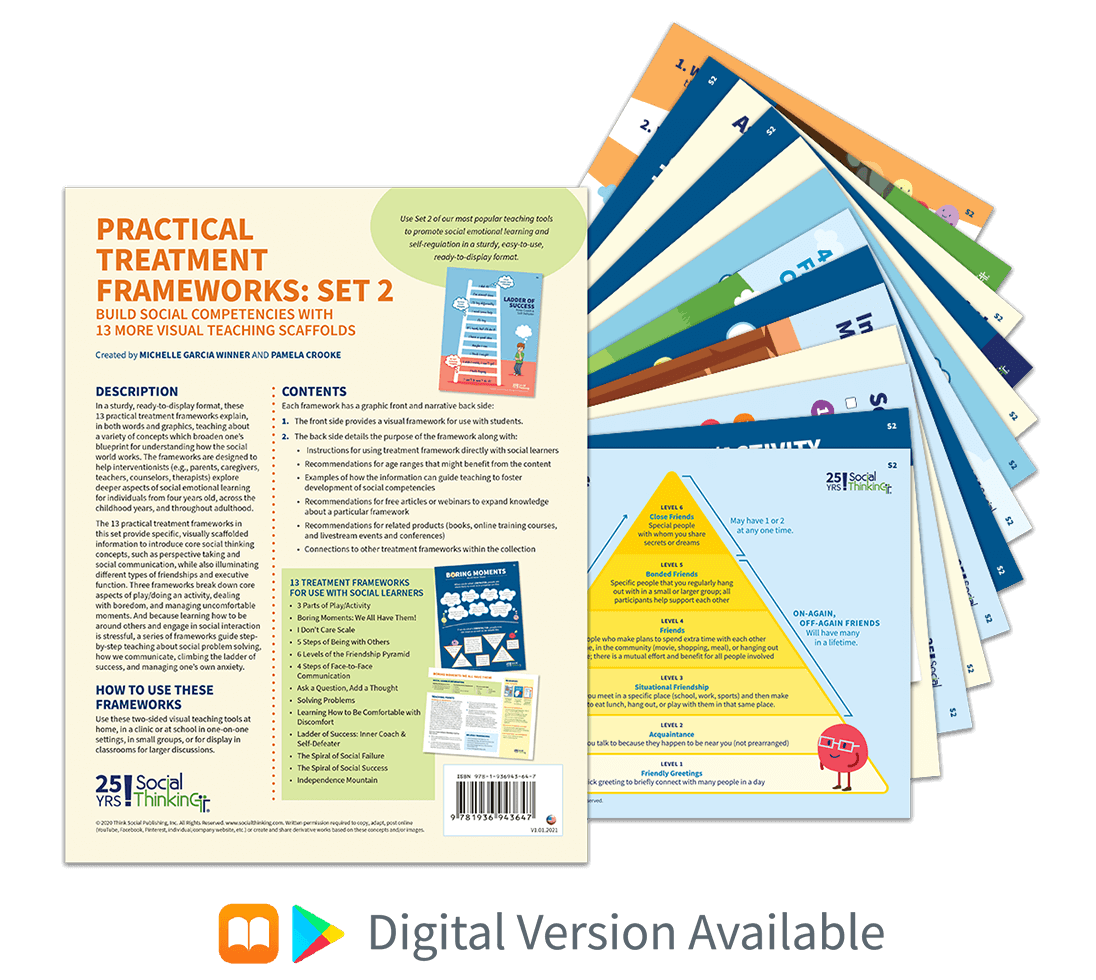

When my clients feel awkward trying new organizational or social tasks, I encourage them to be “comfortable with discomfort” since growth often comes from pushing ourselves to do things that don’t feel easy for us. This was such a popular mantra at our clinic we developed a visual framework to help put a graphic to the words.

Tools I find helpful when working with clients who feel they “can’t” for a variety of reasons include but are not limited to:

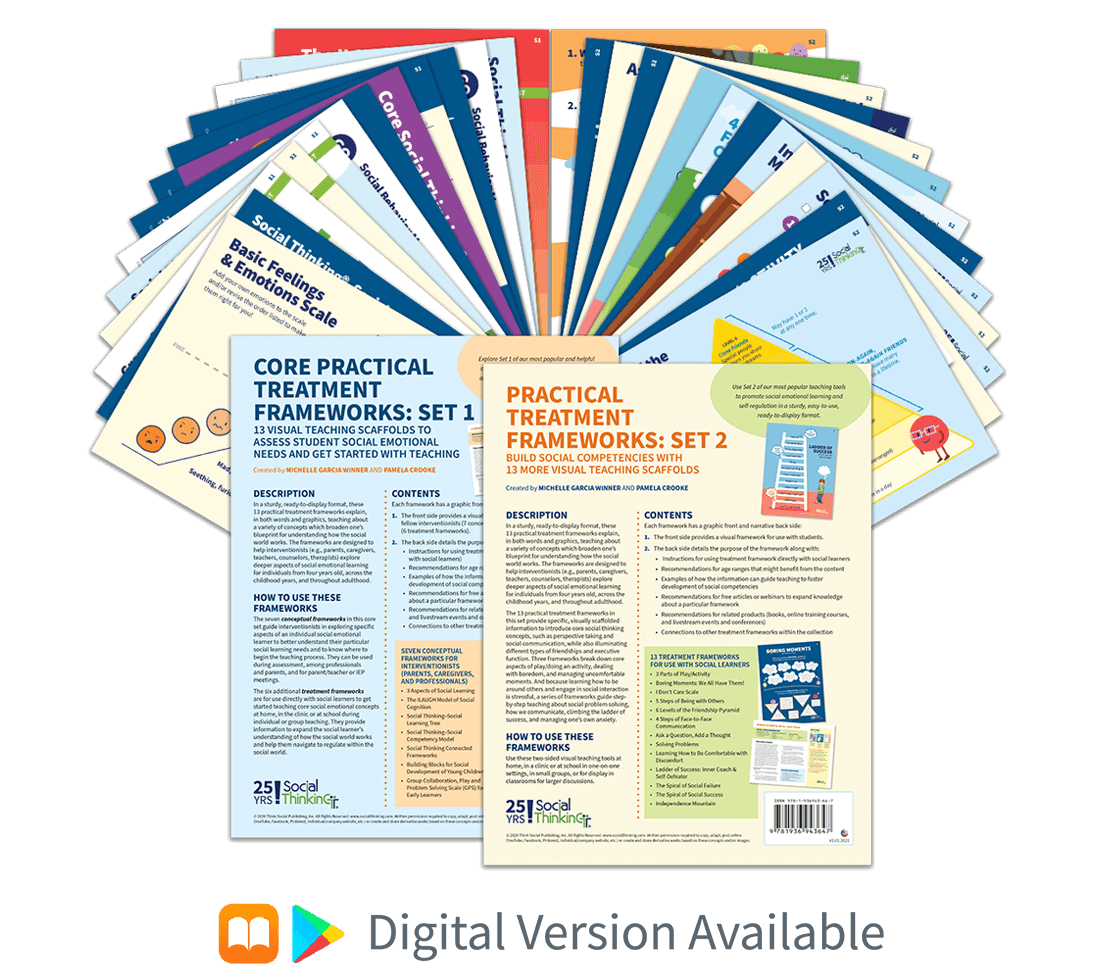

- Learning to Be Comfortable with Discomfort (teaching framework included in Social Thinking Frameworks Collection Set 2). Working toward goals can feel uncomfortable at times and that’s okay. Often our growth comes from putting ourselves in a situation that stretches our comfort zone. Download the Learning How to Be Comfortable with Discomfort teaching framework.

- 5 Steps to Getting Things Done (free downloadable Thinksheet). A basic overview of how we move toward executive functioning:

- Develop a goal: something you think about accomplishing.

- Develop your action plans: have a series of sequenced or parallel action plans to carry out across a period of time.

- What’s your plan to carry out your action plans?

- Self-regulate your behavior and emotions to carry these out.

- Stay flexible through all steps! Do you need to modify any part of the above now that you’ve thought through it?

As part of this process, it helps to recognize the difference between one’s inner coach and one’s self-defeating voice inside one’s mind.

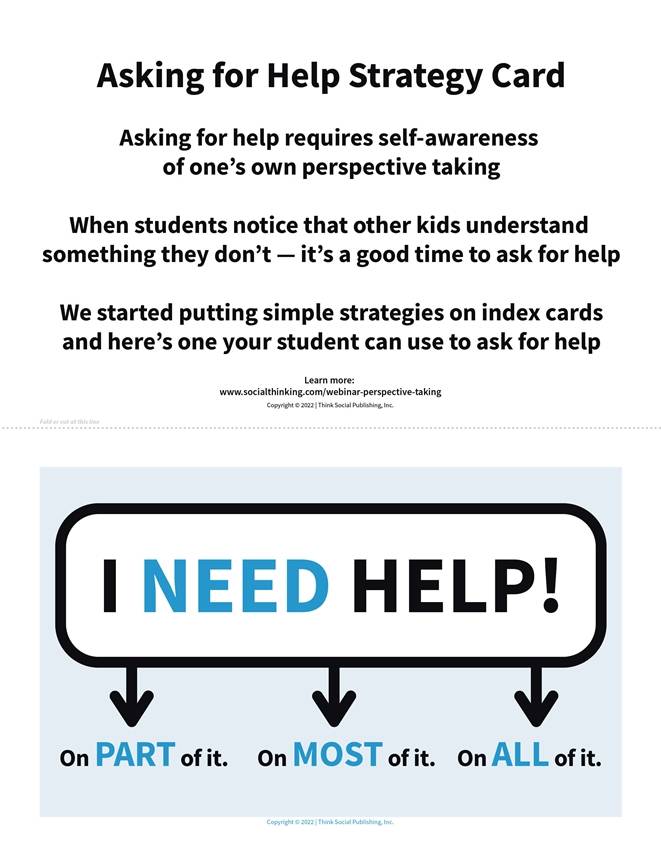

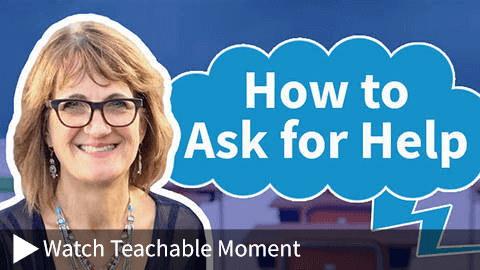

- Asking for Help (free downloadable Thinksheet). If you are reluctant to ask for help or clarification, recognize that you are usually pleased when people ask you for help. When we can share our vulnerabilities, we tend to build relationships. See the Thinksheet below to learn more about engaging in this process.

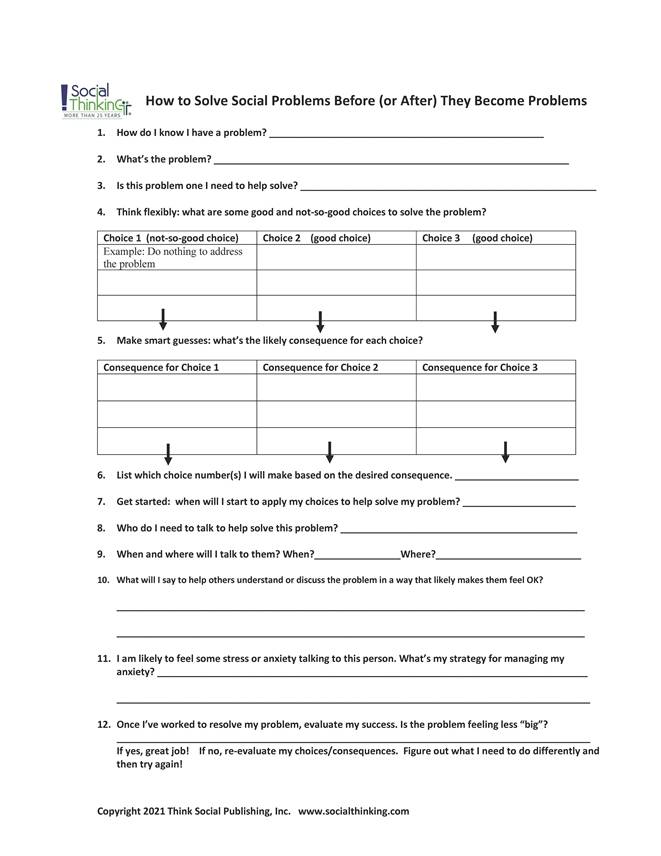

- How to Solve Problems Before (or After) They Become Problems (free downloadable Thinksheet). Not sure how to handle something? The goal of this Thinksheet is to deconstruct the problem-solving process by helping you identify and then choose possible solutions and related consequences and the plans you need to put in motion to actually help yourself solve the problem.

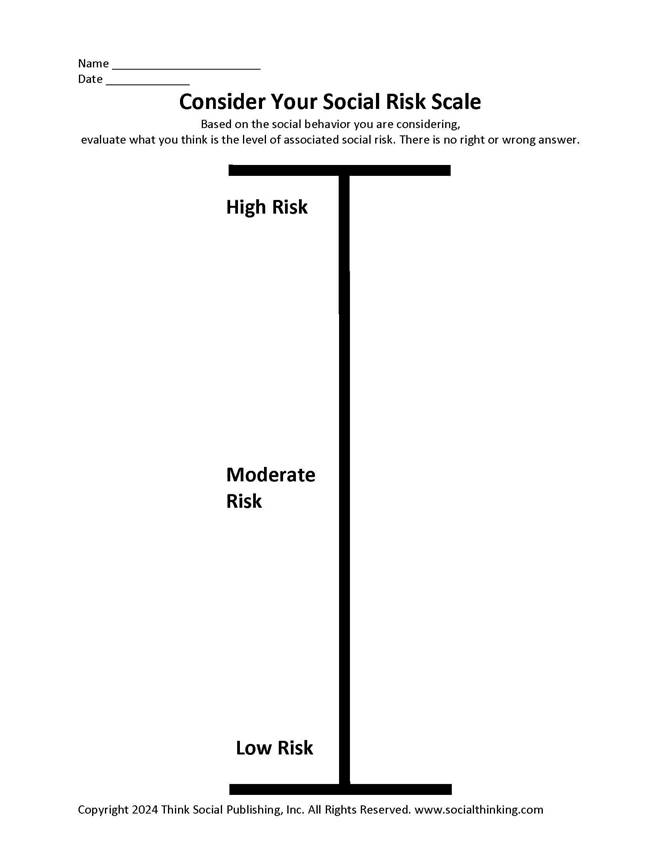

- Consider Your Social Risk Scale (free downloadable Thinksheet). This simple scale is used for people to assess the level of “risk” it will involve for them to try a new routine, behavior, or doing something that stresses them out that helps them meet their goals. If what a client needs or wants to do may cause them to worry, feel stress, anxiety, or discomfort, but they have the competencies to do it successfully, then consider using the Risk Scale. When my clients feel uncomfortable, even though they recognize they have the competencies, I ask them a simple question: What’s the risk? Using the Risk Scale, they most often realize there is virtually no risk in doing whatever it is they are thinking about, and this is a big step forward in finding their motivation.